A man who played two seasons for the Trail Smoke Eaters in the 1940s and broke the NHL’s colour barrier should be inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame, supporters say.

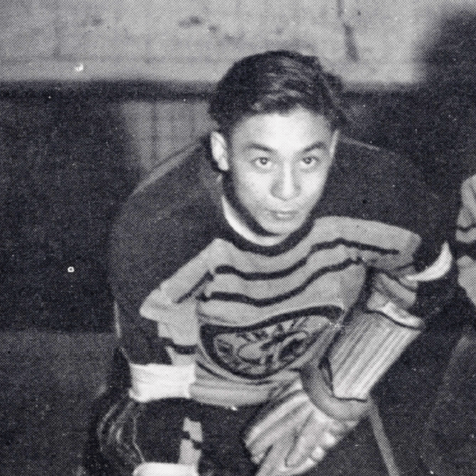

Larry Kwong, who died in 2018, became the first non-white player and first player of Asian descent to play in the NHL when he skated for a single shift with the New York Rangers in 1948. However, that achievement was tempered by a widely-held belief that, given his talent, his major-league career should have been much longer.

“That one game was his greatest triumph and his greatest disappointment,” says Chad Soon, a Vernon teacher who is among those pushing for Kwong’s addition to the Hall of Fame as a builder.

“But still it was such a monumental thing. When you consider how far he had come, we’ve got to celebrate that milestone. Yeah, it was a minute but it was like going to the moon … I think it’s time for him to get his due.”

Before and after his lone NHL game, Kwong had a standout career as a forward in minor, senior, and minor pro hockey, which passed through Trail.

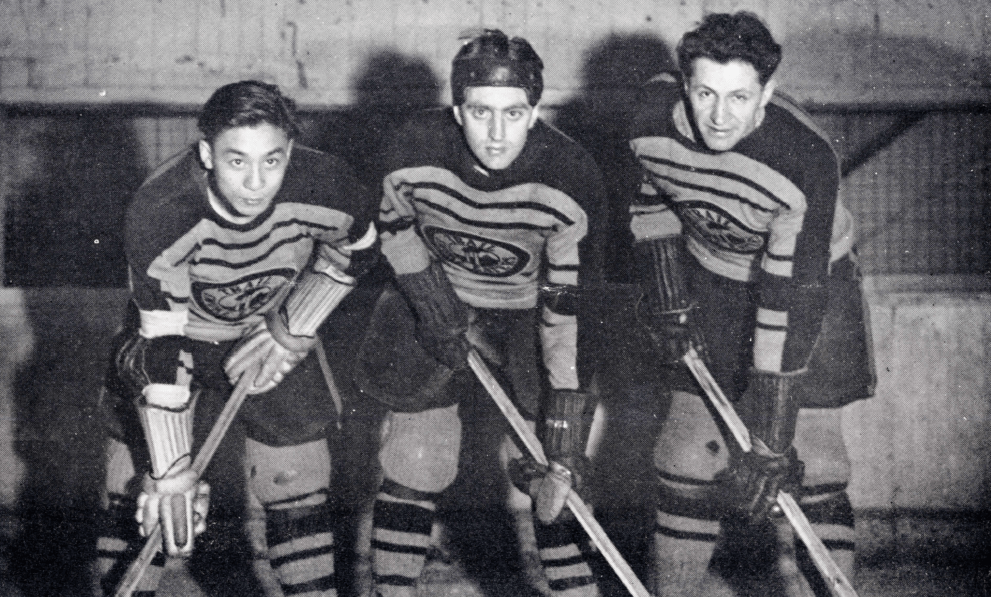

Kwong grew up in Vernon, where he helped his minor team to a couple of championships. In 1941, at age 18, he joined the senior Smoke Eaters, who were two years removed from winning the world championship. With them, he honed his game with help from greats like Ab Cronie.

Lured to town, like other players, by the promise of a smelter job, he arrived to find there was no position for him after all. Kwong was told he was too young. Instead, he went to work as a bellhop at the Crown Point Hotel, a job he didn’t relish, for it isolated him from his teammates. Later he learned the smelter simply refused to hire Chinese Canadians.

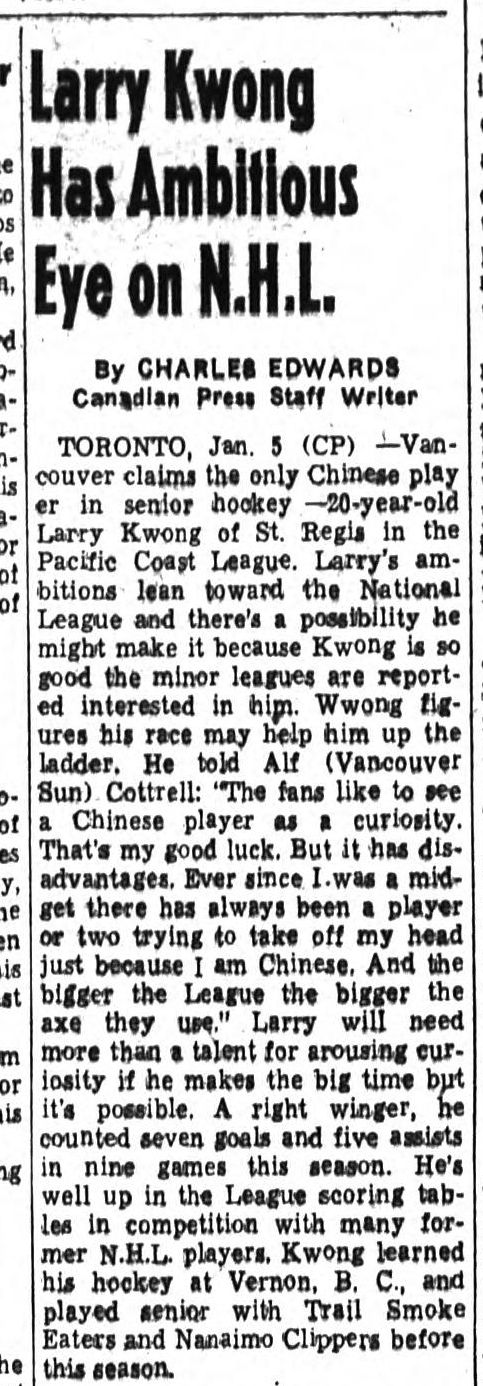

Despite the discrimination he faced, Kwong proved popular on the ice. But the league folded at season’s end due to the Second World War, and Kwong had to find another place to play. He went to the Nanaimo Clippers for a year, then joined Vancouver St. Regis.

In early 1944 he told a reporter of his NHL ambitions. “The fans like to see a Chinese player as a curiosity,” he said. “That’s my good luck. But it has disadvantages. Ever since I [played] midget there has always been a player or two trying to take off my head just because I am Chinese. And the bigger the league the bigger the axe they use.”

“Back in those days, hockey was known as a white man’s game,” Soon says. “The NHL reflected that. He felt he was just another Canadian kid so he had that same dream as so many other kids to make the NHL one day. What incredibly long odds against him, but he persevered.”

Later that year Kwong was drafted into the army and went to Red Deer to serve and play on a military team. The Smoke Eaters came back to life in 1945, and with his discharge, Kwong returned for another season with them, this time as a first-liner. The team program said he “won the hearts of Trail hockey fans with his clever play and brilliance around the net.”

He scored the winning goal at the Savage Cup that year, giving Trail the B.C. senior championship.

As a veteran, Kwong was able to vote, a right denied to most other Chinese Canadians, who could not bring family to Canada either, until the Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1947.

“Chinese had very limited prospects,” Soon says. “That’s why Larry was such a big deal. He was rising up the hockey ladder and finding fame and success when that had been so elusive.”

For Soon’s grandfather, who was born in Vancouver, Kwong provided hope that “the doors would one day open, not just in hockey, but in other fields. That Canada would be a land of opportunity for all people.”

From Trail, Kwong turned pro, attending New York Rangers training camp, where there was reportedly “a great deal of interest” in him. Recently retired general manager Lester Patrick was impressed, while a scout said Kwong “would be a great drawing card in New York.”

Indeed, Kwong remained in New York and helped draw big crowds, but it was for the Rangers’ farm club. There he remained for the next three seasons, leading the team in scoring in 1947-48.

On March 13, 1948, the Rangers called him up for a game against Montreal where he played a single shift at the very end. He was then passed over for further big-league opportunities that went to less productive teammates instead.

The following season, Kwong signed with a team in the Quebec senior league, where he was again a top scorer and league MVP. He later played and coached in Europe.

When Soon was young, his grandfather told him what a hero Kwong had been in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Much later, Soon phoned Kwong and then visited him in 2008 in Calgary, where he viewed his collection of photos and scrapbooks.

When Soon moved to Kwong’s hometown of Vernon, he was surprised his story was not better known. Late in life, Kwong did get some belated recognition. He was inducted into the Okanagan Sports Hall of Fame, the BC Sports Hall of Fame, and the Alberta Hockey Hall of Fame, among other honours.

“But I still feel like that’s not enough,” Soon says.

The campaign to name Kwong to the Hockey Hall of Fame centres around an online petition launched a couple of weeks ago that has so far collected over 7,000 signatures.

Public nominations are due in March, which will coincidentally mark the 75th anniversary of Kwong’s NHL debut. Soon hopes one of the 18 selection committee members will champion Kwong’s induction. He takes it as an encouraging sign that Herb Carnegie, an outstanding Black star, was posthumously added to the Hall of Fame this year as a builder.

(While Kwong may not belong to the Hall of Fame himself, one of his sweaters is already there. His family donated one he wore for the Nanaimo Clippers, which now forms part of an exhibit called The Changing Face of Hockey – Diversity in Our Game. His family still has his Smoke Eaters sweater.)

Although Kwong made the best of any situation, Soon said it did bother him that people occasionally teased him that his NHL career only lasted a minute, not realizing how much he overcame to get that far.

“When it’s your childhood dream, you can’t forget your dream being crushed like that. To his credit, he did not have a negative attitude. He kept showing his character in everything he did.”

You can listen to the full interview with Chad Soon below.