More than 20 years ago, author Lily Chow set out to learn about the settlement of Chinese Canadians in the Kootenays.

The Victoria author had already written two well-received books on Chinese immigration to BC: Sojourners in the North and Chasing Their Dreams: Chinese Settlement in the Northwest Region of British Columbia.

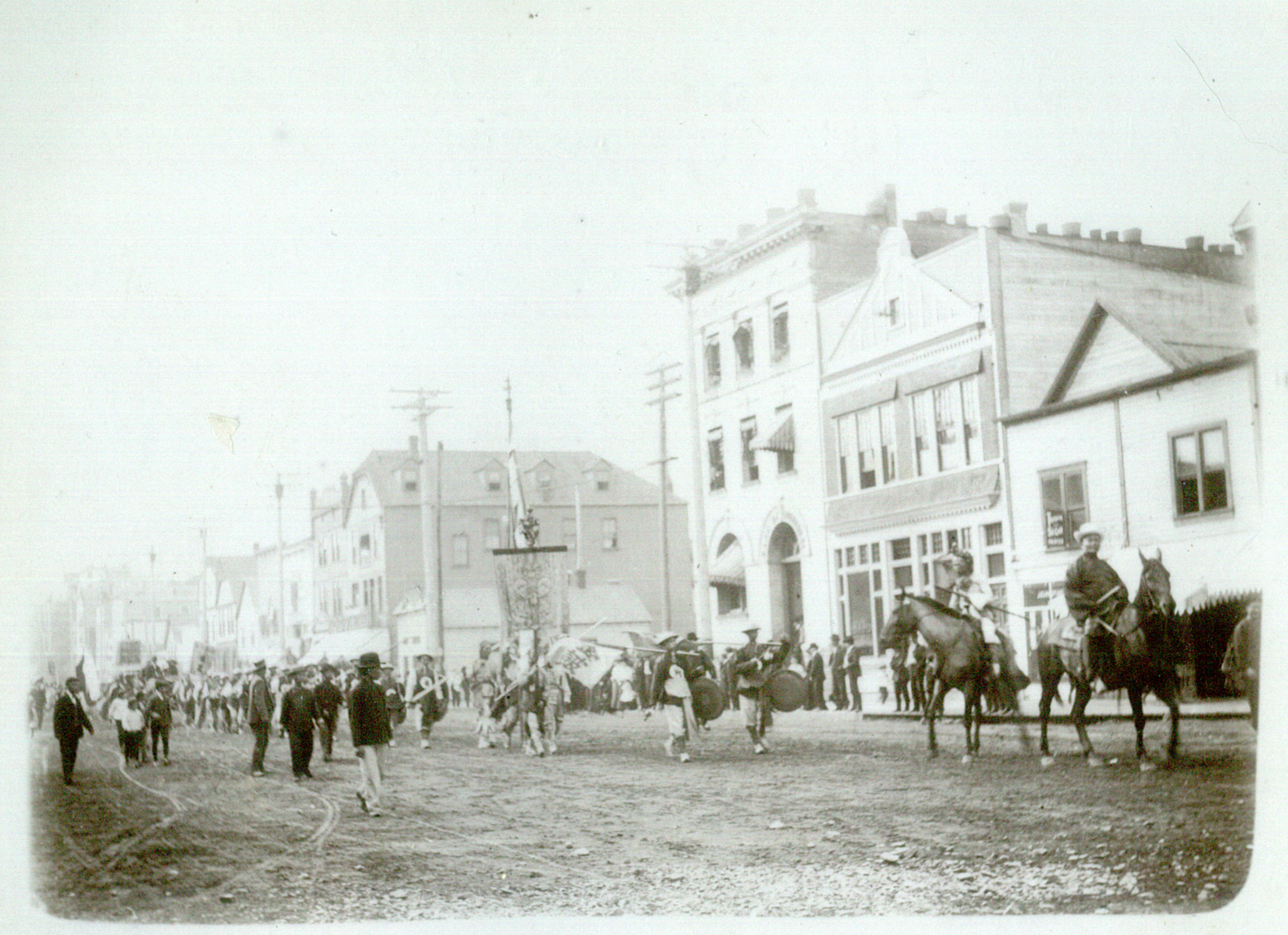

In August 2001, she went to Revelstoke, close to where the Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental line was completed in 1885. Thousands of Chinese workers were employed in its construction, often in terrible conditions, at great peril, and for half the wages of their white contemporaries.

“How hard they had to work to make a life for themselves and how difficult the challenge was to send money to support their families in their hometowns, mainly in Guangdong,” Chow says. “Many of them died and nobody cared.”

Those men were subject to what Chow calls a “push-pull” phenomenon: a push from a country that through civil strife seemed to encourage its own citizens to leave and the pull of precious metals in other nations. Malaysia had tin. Australia and Canada had gold. And the Kootenays specifically had silver and coal.

“All these minerals would help them to gain a better living and to get wealthy so they can support themselves as well as their families at home,” she says. At least that was the hope. Chow’s father-in-law was one of those men who came to Canada to work on railway construction and he stimulated her to ask questions.

In Revelstoke, she visited the local archives and cemetery and conducted interviews, then proceeded to Nelson, Rossland, Cranbrook, and Fort Steele to do the same. However, at the end of her trip she felt overwhelmed with the information she’d collected and set it aside.

Fast forward to June 2019. While attending the annual conference of the BC Historical Federation in Courtenay, Chow was shocked to learn of the death of Cameron Mah, a prominent Nelson resident who was one of her interviewees.

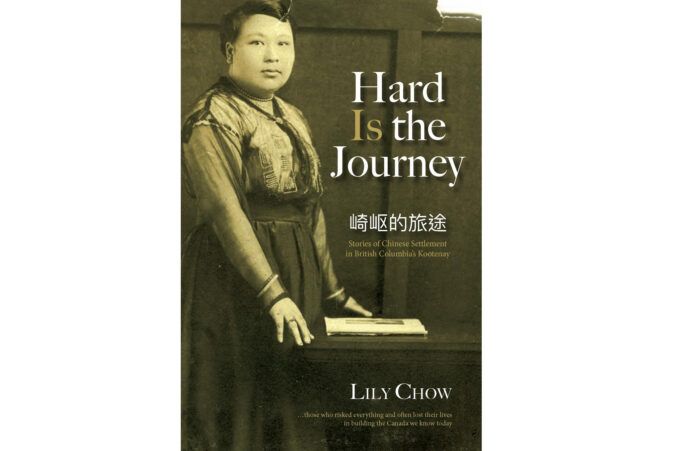

That prompted her to revisit her old research materials, supplement them with new findings, and write Hard is the Journey: Stories of Chinese Settlement in BC’s Kootenay, which looks at five Kootenay communities that once had sizable Chinese Canadian communities.

After the CPR was completed, men found their way into other industries like placer mining and market gardening, while others started businesses like laundries and restaurants.

In Nelson, Mah shared with her the story of how he came to Canada alone as a boy in the 1950s and eventually became a well-known chef, restaurant proprietor, and ambassador for Nelson’s Chinese Canadians.

“He was such a good friend,” Chow says, adding that Mah also acted as an interpreter in citizenship ceremonies. Once, he translated as a judge asked a Chinese woman: “Why do you come to Canada?” She replied “I’m raising a future prime minister.”

Chow laughs: “As Cameron says, the judge almost fell off of his chair!”

While it’s a cute anecdote, Chow notes Chinese Canadians in BC historically faced disenfranchisement and profound racism that restricted where they could live and how they could earn a living.

“The early Chinese were discriminated against. They were prejudged by Europeans. Of course the British were the main culprit. But they could not go home by themselves because they had no funds.”

Chinese Canadians were denied the right to vote provincially and federally until 1947. From 1885 to 1923, a head tax restricted Chinese immigration to Canada, and from 1923 to 1947, the Chinese Exclusion Act banned it almost entirely. In 2006, the federal government formally apologized to those who paid the head tax and their families.

What has been written about Chinese Canadians in the Kootenays until now has been scattered across many different books. Chow’s work is the first widely-available volume devoted to the subject.

Her book benefited from her fluency in English, Cantonese, and Mandarin. She was able to conduct interviews in multiple languages and translated Kootenay-related items from the Chinese Times, a newspaper published in Vancouver by the Chinese Freemasons Society.

Among others profiled: the Lum and Ban Quan families of Wild Horse Creek; the Wong Kwong and Yee Von family of Revelstoke; and laundry operator Mar Sam and market gardener Charlie Bing of Nelson.

Chow presents these individual stories within the larger context of political events in China that had repercussions an ocean away in Canada.

“The thing I really wanted to know was how our ancestors made life possible,” she says. “I think people have to be proud of themselves and their parents and ancestors who came here to make life work for them. Without them coming over here they would not be able to enjoy and treasure the way of life in Canada.”

Chow herself was born in Malaysia and came to Canada in 1967. She taught for many years in Prince George and at the University of BC and is an Order of Canada recipient. She is also the author of several other books including Blossoms in the Gold Mountains: Chinese Settlements in the Fraser Canyon and the Okanagan.