A man whose mother and grandfather were the last permanent residents of k’pit’els, the Sinixt village at the confluence of the Columbia and Kootenay Rivers, has died at 91.

Lawney Reyes, a noted artist and author, was present in 2009 as a stone monument to his family was unveiled at the site, also known as the lower Brilliant flats. At the same time, he accepted an apology from Doukhobor leader J.J. Verigin for the treatment of his ancestors nearly a century earlier.

“The memorial was very meaningful to him,” says Muriel Walton, who helped organize its creation as a member of the West Kootenay Family Historians.

“He was very happy to have that memorial stone there to mark k’pit’els, where his ancestors lived for centuries. He kept in touch with us. He would come back every time he wrote another book.”

Reyes’ final visit to the area was earlier this year, although those he met with did not realize at the time that he was saying goodbye to them and his ancestors’ landscape.

Reyes’ grandfather was Pic Ah Kelowna (White Grizzly Bear), also known as Alex Christian. During an annual huckleberry picking trip to Red Mountain in 1913, Reyes’ mother Mary was born.

However, they returned home to k’pit’els to find a fence around their home.

Although the family’s land was staked as a reserve in 1884, bureaucratic bungling or oversight allowed a Crown grant to be issued to John Carmichael Haynes, a justice of the peace and customs officer from Osoyoos.

In the 1910s, community Doukhobors arrived in the area and bought the land. The Christians’ requests to have a portion formally set aside for them were rebuffed.

As Reyes later recounted, “the Christian family could not understand how the land they had occupied for generations could be bought from under them without their knowledge or consent.”

Alex’s wife Teresa died of pneumonia and was buried next to her other three children. In 1919, feeling unwelcome in their own home, Alex and Mary left to join relatives at Kettle Falls, Wash. Alex died five years later of tuberculosis and Mary went to live with foster parents.

Mary married Julian Reyes, a Filipino man, and Lawney was born to them in 1931, the eldest of three children. He was raised on the Colville Reservation and often looked after his younger siblings.

During construction of the Grand Coulee Dam, the family started a restaurant and hired Harry Wong as a cook. Julian and Mary later divorced and Mary married Wong.

Reyes was sent to the Chemawa Indian boarding school in Oregon, where teachers recognized his exceptional artistic talents. In 1959, he graduated from the University of Washington, where he majored in interior design, and went on to a distinguished career as a prolific sculptor, designer, and curator.

In retirement, he wrote several memoirs, the best known of which is White Grizzly Bear’s Legacy: Learning to be Indian, in which he wrote about his childhood and recounted the Christian family’s frustration toward the government and Doukhobors over the “invasion” of their land.

Selkirk College instructors Myler Wilkinson and Duff Sutherland contacted Reyes, wondering if he would attend a symposium on Sinixt/Doukhobor relations in 2007. However, he declined.

“It would be improper for me to extend my pardon to a people who have taken the Christian family land,” he told them. “As a result of losing their property, and the only home they had, my grandmother, Teresa Bernard Christian was heartbroken and died at a very early age.”

Wilkinson, Sutherland, and others later proposed a monument to the Christian family at k’pit’els. As part of those efforts, Muriel Walton read White Grizzly Bear’s Legacy and began corresponding with Reyes.

“He encouraged us to go ahead and make the monument,” she says. “That gave energy to the project. As an artist and author he offered his designs and helped with the text.”

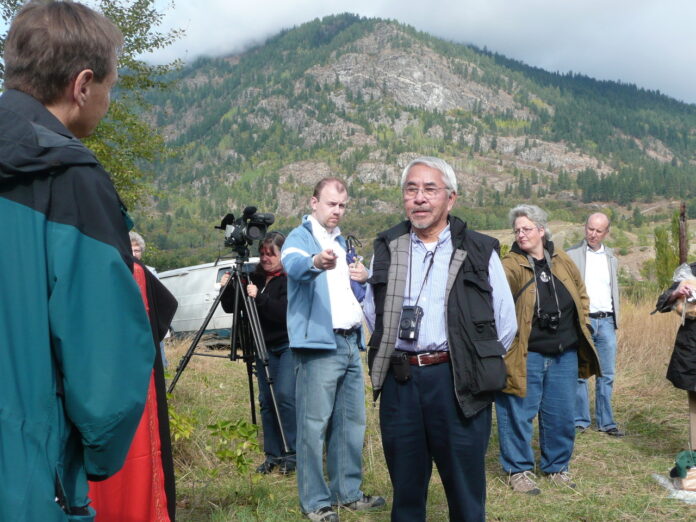

In October 2009, Reyes travelled with family members from Kirkland, Wash. for the unveiling. The night prior, he spoke at the Mir Centre for Peace, a former Doukhobor communal home on the Selkirk College grounds, just across the river from k’pit’els.

He met with J.J. Verigin, executive director of the USCC, the largest Doukhobor organization in Canada, and a direct descendant of Peter V. Verigin, leader of the community Doukhobors at the time of their purchase of the lands at Brilliant.

The next day, as part of the ceremony dedicating the stone monument, Verigin asked Reyes again if he could apologize to his family. This time he consented.

Verigin knelt near Reyes and pressed his forehead and arms to the ground. As Wilkinson and Duff recounted, the 60 or so people present “understood that, within the Doukhobor culture, this was the deepest form of respect one human soul can pay to another.”

After a moment, Reyes responded: “I am not an emotional man, but what you have given your people today has moved me. I accept your apology.”

Thereafter, Reyes made several more visits to the area. Each time he completed a new memoir, he brought a copy to Muriel Walton and her husband John, and another copy for Selkirk College, where he became close friends with president Angus Graeme.

In May, Reyes and his longtime editor and companion, Therese Johns, drove to Castlegar to hand-deliver copies of his latest work.

The Sinixt are also known as the Lakes people and Reyes wanted to see the lakes his ancestors once plied in sturgeon-nosed canoes. The Waltons drove him to Slocan Lake and, on the same day, to Kootenay Lake.

“The lake was in its splendor,” Muriel says. “The sun was shining on it. And Lawney was thrilled to be standing beside another of his lakes.”

They returned to Castlegar, where Reyes visited with Graeme. After an hour together, Reyes and Johns drove back to Washington state.

Last week, the Waltons learned Reyes had died on Aug. 10. Muriel says they didn’t realize during his visit that he was ill.

Among other relatives, Reyes is survived by his son Darren, daughter Lara, companion Therese, brother Harry, sisters Teresa and Laura, and several grandchildren.

The Christian monument at k’pit’els stands as a symbol of reconciliation and, as Wilkinson and Sutherland wrote, has itself “become a site of cultural pilgrimage.”

Listen to the full interview with Muriel Walton here:

Read more:

• Doukhobor-Sinixt Relations at the Confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers

• Being on the Land: Histories at the Confluence

• Closing of the Circle: Descendants of Alex Christian — the White Grizzly