A group representing different segments of the Doukhobor community in Canada is calling on the provincial government to follow through on an apology and compensation for Sons of Freedom children removed from their parents in the 1950s.

The open letter to Attorney General Niki Sharma, under the letterhead of the Council of Doukhobors in Canada, includes signatories from BC and Saskatchewan.

“The impact upon the survivors and their families continues to this day so this letter is one initiative toward justice, added to the many tireless initiatives by the New Denver survivors and their families spanning decades,” said Ahna Berikoff, who was among the signatories.

The BC Omudsperson’s office recently published a report on the subject, following up on an investigation from 1999. The government’s response indicated an apology could come this fall, but it was more vague on compensation.

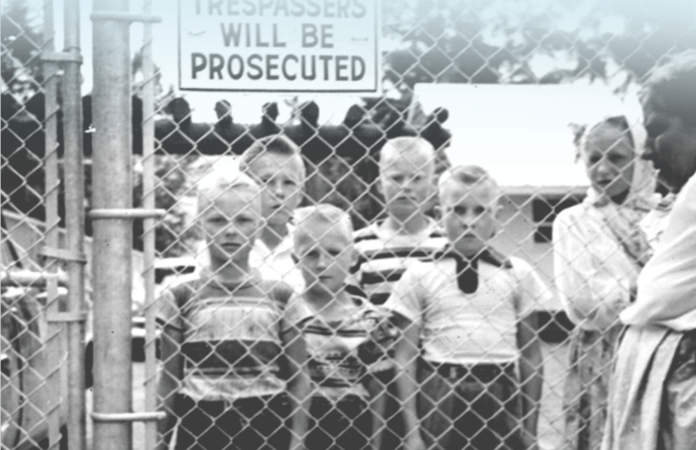

About 200 children were removed from their parents and sent to residential school in New Denver from 1953-59. In 2004, the province offered survivors a “statement of regret,” in the legislature but not an apology.

Berikoff said the issue unites Doukhobors from different groups and areas.

“We all agree this initiative is very significant. Now’s the time to exert some pressure on the government. Even though they say yes, there will be an apology, we’ve found time and time again there have been empty promises to acknowledge this injustice.

“I think an apology is a powerful symbol to admit an atrocity was initiated and enacted by the government. With an apology, healing could take place on a cultural and collective level.”

Walter Perepelkin, a director with the Krestova Doukhobor Society, who is another signatory, was 10 when he and his seven-year-old brother were taken to New Denver. A newspaper report said until then, they had escaped 21 visits from the police.

“We were asleep at the neighbours,” he said. “I heard a whole bunch of noise. When I opened my eyes, well there was probably half a dozen police and they took us.”

They spent the night in Nelson and the next day appeared in front of a judge who directed that they be taken to New Denver.

Perepelkin said his experience was “not good at all. Everything was strange.” He had never been in school before. On his first day, he couldn’t understand what his teacher was saying and he asked a friend to explain.

“She noticed and she asked him to stand up. She started slapping him for helping me,” he said.

“Then she stood me in front of the class. I can’t remember what she was saying, but I couldn’t understand anyway. She sent me to the principal, who gave me the strap. That was the start of my New Denver [experience].”

Perepelkin was part of calls for an apology that started in 1999 with then-ombudsperson Dulcie McCallum. A committee sent over 100 letters to survivors and found the majority wanted her recommendations implemented in full.

But Perepekin said rather than dealing with the survivors as a whole, the government worked with a smaller group on a monument project in New Denver.

“The majority of the people said we don’t want it,” Perepelkin said. “People were very upset. You don’t deal with small groups. Deal with everybody and everybody equally. Don’t pick and choose.”

The monument got as far as an unusual picnic table in New Denver, which is still there, but without any signage to denote its significance.

Perepelkin said compensation is important, but he is mainly interested an apology and an explanation.

Despite what the government recently wrote, he’s not getting his hopes up, for he has heard before that an apology might be in the offing, including on a visit by then-premier Ujjal Dosanjh in the early 2000s, only for things to come to naught.

“We kept hearing there would be apologies but nothing materialized. What can we expect right now?”

Perepelkin laments that even if an apology does come, it will be too late for many people to hear it, including his brother, who took his own life in the mid-1990s.

“I can’t say that was the reason, but it happened,” he said.